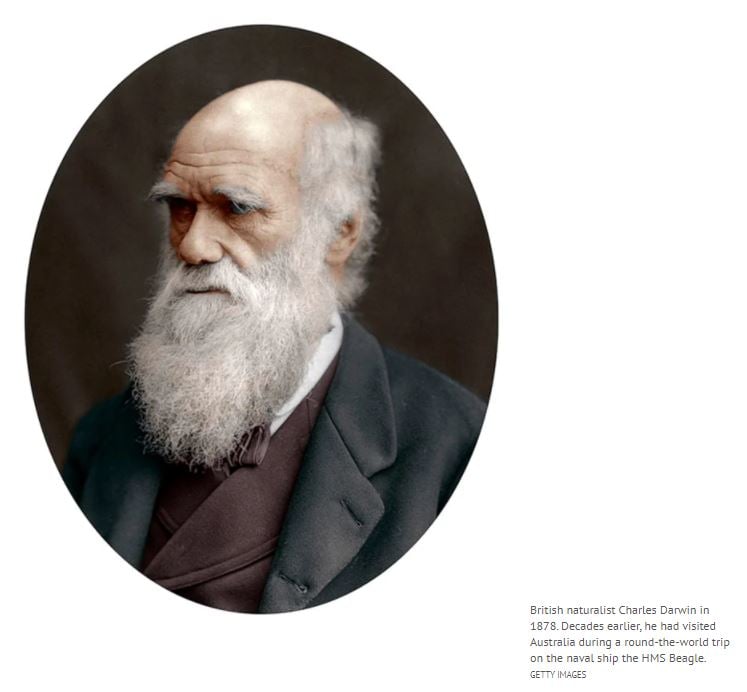

Australia’s wildlife was so weird to the 19th-century scientists of the northern hemisphere that it caused one of them, a devout Christian by the name of Charles Darwin, to question his God’s creation.

“A disbeliever in everything beyond his own reason might exclaim, ‘Surely two distinct Creators must have been [at] work; their object, however, has been the same’.”

Darwin wrote in 1836, after visiting Coxs River at Wallerawang in NSW, after a day’s kangaroo hunting, during which he had stumbled on a potoroo, parrots and a platypus, had blown Darwin’s mind.

He hadn’t known it then but most of the plants and animals he had encountered had spent 40 million years evolving their own unique solutions to a common conundrum: how to survive and prosper. The longer Australia’s plants and animals spent on an island in glorious isolation – and 40 million years is a decent whack of time even in the slow game of evolution – the further its species reproduced along their own evolutionary branch, so that their solutions to these issues were, compared with the rest of the world, odd.

More than 80 per cent of Australia’s nearly 400 mammal species, from flying marsupial sugar gliders to truffle-eating miniature kangaroos, are found nowhere else in the world. The same goes for about 95 per cent of nearly 1000 reptile species, from blue-tongued lizards to thorny devils, and for more than 90 per cent of the nearly 300,000 species of invertebrates, of which fewer than 15 per cent have been formally described.

“It’s not just the sheer numbers of species that matter in Australia,” says the Wilderness Society’s Tim Beshara, “it’s how totally unrelated these species are to everything else on the planet. Australia’s flora and fauna species don’t just represent a few leaves on the tree of life, they represent entire branches and some of the trunk.” This means that when just one species becomes extinct in Australia, a significant part of Earth’s evolutionary history is lost – there is no near cousin, nothing quite like it, to fill its niche.

Our plants and animals are, Beshara says, “disproportionately special”.

So how did our flora and fauna get to be so unique? What’s so unusual about creatures such as kookaburras, lyrebirds and thorny devils? And what are the consequences if they become extinct?.jpg?width=1897&name=Antarctic%20beech%20(Nothofagus%20moorei).jpg)

How did our plants and animals end up on their own?

The Gondwana supercontinent, comprising Africa, South America, India, Madagascar, Australia and New Zealand, began to slowly break apart 165 million years ago. Australia and South America remained linked to Antarctica by land bridges covered in beech forest over which marsupials roamed. Australia drifted away from Antarctica about 40 million years ago, which severed the link to South America as well.

Further north, Australia and New Guinea, which sit on the same tectonic plate, were drifting northwards as they still do today: the Australia-New Guinea continental plate is colliding with Eurasia, forcing up the New Guinea Highlands and buckling downwards into a now-submerged land bridge across the Torres Strait. That land bridge sank just 12,000 years ago, at the end of the last Ice Age, when melting glaciers filled in the trough – which is why there are common species among Australia, Papua New Guinea and the Indonesian provinces to its near west, notably the cassowary as well as many birds, echidnas and tree kangaroos.

Fossil records reveal Australia’s ancient ecological isolation. “All of the other continents,” says eminent Australian paleontologist Michael Archer, “had physical connections between each of them, meaning that they have been exchanging biota [animals and plants] back and forth.

“We have, for example, camels in South America and camels in Asia. The camels in South America are the llamas and alpacas. South America has had elephants and lions, all the same things that were spread all the way across the other continents.

“Essentially, the other continents have had a shared genome for much of the last 65 million years, since that meteor hit the Earth and obliterated the non-flying dinosaurs, when there was a massive explosion in the northern hemisphere of placental mammals.”

What kinds of animals are unique in Australia?

In 1859, British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace drew a line on a map through the Indonesian archipelago representing his realisation of a geographic split in mammal evolution. In the west were placental mammals, nourished by their mother’s uterus, and in the east were marsupials, which suckle their young in the pouch, and monotremes, which lay eggs. The great gulf in evolution is cut sharply on the map. On the ground, from the northern tip of Lombok, on the marsupial side of the Wallace Line, the lands of placental mammals can be glimpsed across a narrow strait just 35 kilometres away in Bali. Wallace’s contemporary, Thomas Huxley, altered the northern tip of the line to incorporate the Philippines, which also has a lot of endemic wildlife.

Where deer evolved in the northern hemisphere, kangaroos cropped up in Australia. Primates evolved in Africa and migrated into South and Central America as well as Asia, many growing limbs to exploit fruiting trees. But in Australia marsupials fill that role, with tree kangaroos and cuscuses that swing from limb to limb. Even more ancient animal lineages remain within the echidnas and platypuses, monotremes that uniquely among land animals use electro-location to sense prey and even retain the reptilian traits of egg-laying and legs on the sides of their bodies rather than underneath, as with mammals.

Pioneering ecologist Professor Christopher Dickman says marsupials arrived in Australia via the land bridge from South America about 40 million years ago and there was a “spectacular radiation”, meaning the animals got busy evolving into a wide array of species. “Because of the integrity of the radiation, we’ve got all of these forms that really don’t occur anywhere else. Certainly, there are marsupials in South America, but they’re all little guys. They’re all five kilograms at the very maximum,” Dickman says. “The vast majority of them are smaller, mostly omnivorous and they’re pretty similar to each other in many respects, whereas in Australia they’ve been able to radiate into the country’s many environments.”

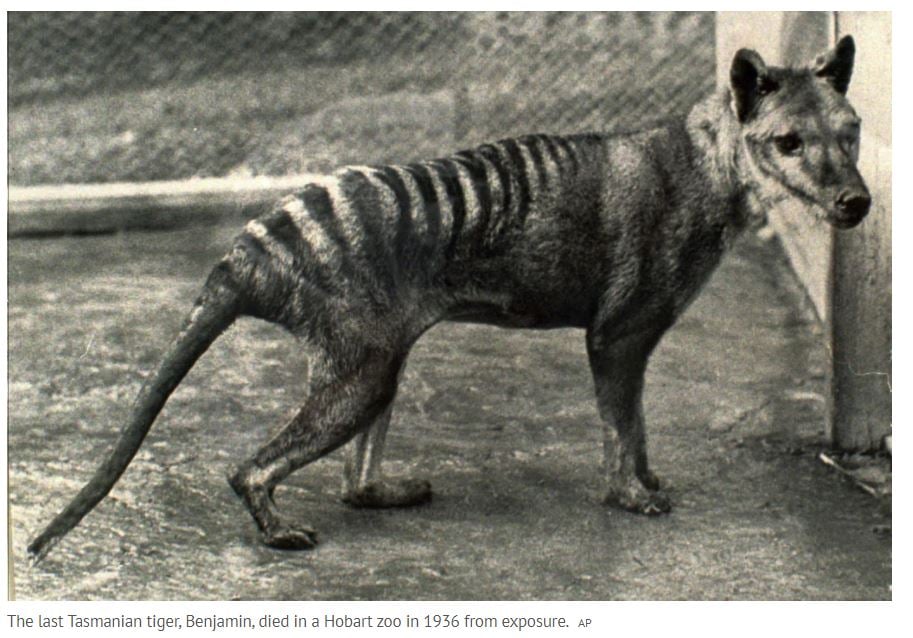

A marsupial lion weighing about 130 kilograms roamed Australia’s forests, the largest ever carnivorous marsupial before it died out 30,000 years ago – about 20,000 years after the arrival of Aboriginal Australians. The next biggest Australian meat-eater that cohabited with humans was the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger, its males weighing in at 20 kilograms; and the next biggest after that is the Tasmanian devil.

Scientists think the thylacine and devil were both extinct on the mainland by 3000 years ago, possibly due to competition with dingoes, introduced between 5000 and 10,000 years ago. But thousands of years before that – about 12,000 years ago – rising sea levels had inundated the land bridge between the mainland and Tasmania, making the latter an island refuge for devils and the thylacine. But Tasmania was no haven once European settlers arrived; by 1936 they had hunted the thylacine to extinction, although the devils survive.

And it wasn’t just the carnivorous marsupials that proliferated. “We’ve got specialist insect-eating marsupials, specialist termite-eaters – which is primarily the numbat – and we’ve got the world’s only specialist fungivore marsupials in the potoroos and bettongs.”

West of the Wallace Line, the aardvark evolved as the mammalian solution to exploiting protein-rich termites but in Australia, in a process known as convergent evolution, the marsupial to fill this niche was the numbat. Numbats are the only marsupials active in the day. They once lived across vast tracts of Australia but have been hunted down by foxes to a small corner of Western Australia.

With no monkeys or lemurs as competition, the tree kangaroo evolved. CREDIT:GETTY IMAGES

With no monkeys or lemurs as competition, the tree kangaroo evolved. CREDIT:GETTY IMAGES

Another case of convergent evolution is the tree kangaroo. In the absence of competition from arboreal primates such as monkeys, lemurs and gibbons, kangaroos adapted to climb trees and eat the fruits and leaves on offer.

Potoroos, which so amazed Darwin, as did their relatives the bettongs, are unusual not just because they’re the only marsupials that dine on fungi – native truffles buried in the soil, to be precise – but also for their role as ecosystem engineers. “In the forest environment, potoroos eat fungi and they move the spores around in the forest,” Dickman says. “They’re the vectors for the spores.”

Fungi have a symbiotic relationship with some plants, where they source necessary carbohydrates from plant roots and in return harvest scarce nutrients from the soil such as phosphorus, nitrogen and potassium, which dramatically improve plant growth. “You lose the potoroos and you lose the ability for the fungi to move around in the forest,” says Dickman. “So in the wake of a disturbance, like a fire or a flood or somebody going through with a bulldozer, if the fungi are not there and the potoroos have gone, plant growth will be much, much slower.”

Did the world’s songbirds really come from Australia?

When Darwin sat down to write after his trip to Coxs River, it was little wonder he questioned how one god could create both those European animals he was familiar with and those creatures he’d witnessed on the western side of the Blue Mountains. “Would any two workmen ever hit on so beautiful, so simple and yet so artificial a contrivance? I cannot think so,” Darwin wrote. Many scientists and historians argue this moment was the genesis of Darwin’s revolutionary theory of evolution, eventually published in On The Origin of Species in 1859.

Even the most mobile of animals, the birds, boast species in the hundreds that are endemic – that is, unique – to Australia. Of the 830 types of bird in Australia, 45 per cent are found only here. What’s more, as biologist Tim Low points out in his outstanding 2017 book Where Song Began, all the world’s songbirds and the most visually appealing birds have Australian roots. “An Australian origin is implied for every songster in an English country garden, for all the chickadees, cardinals and jays in America, for bulbuls, babblers and sunbirds in Asia, and weavers, whydahs and bush-shrikes in Africa,” Low says.

One of Australia’s most spectacular songbirds, the superb lyrebird, also has the deepest evolutionary lineage and retains physical features of the earliest songbirds. The lyrebird’s mimicry is not limited to just about every other bird in the forest but extends to human voices, camera shutters, mobile phones, car horns and even chainsaws. It is also one of the world’s largest songbirds, with a dramatic fantail used in courtship displays. So well adapted are the largely solitary lyrebirds to their forest environments, they have been known to anticipate incoming bushfires by congregating in sheltered gullies and watercourses to survive the flames.

It’s now known songbirds spread out around the globe from Down Under but this fact was only scientifically recognised in 2004, due to the parochial assumptions of the majority of the world’s northern hemisphere-based ecologists. “Going back a couple of decades – maybe it was because of cultural cringe – we always assumed that songbirds must have arrived in Australia and then radiated here. But now we realise that actually the radiation took place here,” says ANU professor of wildlife ecology Sarah Legge.

“Kookaburras are siblicidal – so the chicks, within minutes of hatching, try to kill each other.”

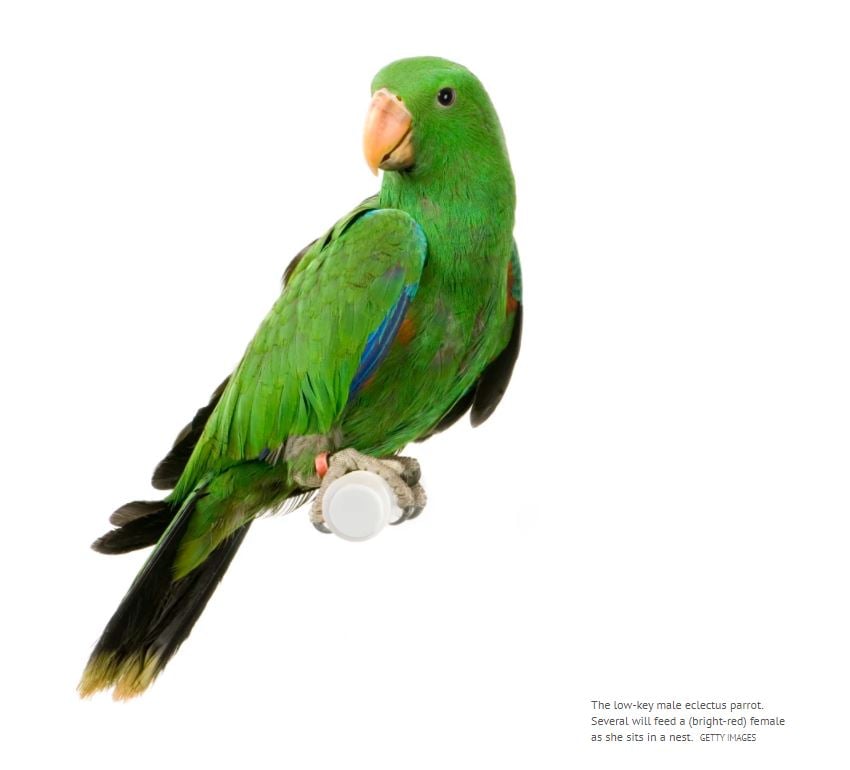

Among the most captivating of these “weird and alternate” birds, she nominates the palm cockatoo and the eclectus parrot, both found in the forests of northern Australia and New Guinea. “Palm cockatoos are the only bird that uses a tool to make music. They get a stick, which they often prune a bit, and they use that to bash the side of their nesting hollows in a rhythm,” Legge says. “That’s way out there, that’s really unusual. What’s really incredible about the eclectus parrot is they’ve got that reversed sexual dichromatism – so the females are bright red and the males are green so they’re more camouflaged. But then the females are also promiscuous, so they’ll mate with multiple males and then sit in the nest hollow for months at a time getting fed by multiple males – they’ve got a really wacky lifestyle.”

Weird bird behaviour isn’t limited to Australia’s remote forests – witness the blue-winged kookaburra. “The incredible thing about them is that, as adults, they’re in co-operatives. Kookaburras live in family groups where the young from previous nestings stay with their parents and help them raise more broods in the following years. But when they hatch in the nest, because usually two or three chicks hatch in the nest, they’re siblicidal – so the chicks, within minutes of hatching, try to kill each other,” Legge says.

“In this one species, you’ve got this most extreme selfish behaviour, I guess at one end of their life. Killing siblings is a big deal because they share genes. And then, at the other end of their life, they forgo their own breeding attempts to help feed and care for their parents’ chicks. They flip from one extreme to the other.”

Why are we losing species then?

The extraordinary uniqueness of Australia’s natural endowment is not well understood, nor is it adequately protected by environment laws, says Beshara. “There is an under-appreciation among politicians, business leaders and even the wider conservation movement about how disproportionately special Australia’s biodiversity is,” he says. “None of the government regulation or industry standards take into account Australia’s special status among nations.

“We are the centre of the world for two out of three major groups of mammals.”

“For instance, platypus and echidnas make up one of the three major branches of the mammal family tree, marsupials make up the second branch, and all of the rest of the cats and bears and whales and rats make up the third and final branch. That means we are the centre of the world for two out of three major groups of mammals.

“To lose a species in Australia means there is a much higher likelihood of losing entire swathes of evolutionary history than a species lost anywhere else. As the world’s most evolutionarily distinct realm on the planet, we have a higher obligation to protect what we have – and currently we are failing to do so.”

Australia has lost 39 species of mammals since colonisation, with the nation’s share of the world’s extinct mammals totalling 38 per cent. The growth in farming and feral cat numbers, for example, is thought to have wiped out the diminutive eastern hare-wallaby, which lived in the grasslands of south-eastern Australia, and the crescent nail-tail wallaby, native to central and south-west Australia, which also fell victim to habitat loss and predation.

All up, about 100 of Australia’s native flora and fauna species, from rare orchids to the Daintree’s river banana, have been wiped off the planet. Four species of frogs and 22 species of birds, including the paradise parrot and the red-crowned parakeet, have vanished forever. Many more creatures are critically endangered. The rate of loss, among the highest in the world, has not slowed over the past 200 years, since the early days of land clearing and the introduction of feral cats and foxes.

University of Sydney professor of ecology and evolution Glenda Wardle says a shift in thinking about conservation is under way: “We don’t just need to keep the ones that are good for giving us medicine, or the ones that give us food and all the rest is somehow dispensable – and maybe put a few in a reserve somewhere. The idea now is that all species have a right to life.”

Ring-fencing reserves for animals in out-of-the-way places not needed for farming, building or mining will not be enough to conserve Australia’s biodiversity, especially in the face of climate change, Wardle says. “Species are evolving, always. It’s not a ‘turn it on, turn it off’ thing. They’re always matching to what the conditions are. And as we’re going through this rapid climate change, we expect more rapid change in some species, in terms of how their traits match the environment.” Research indicates that Australian birds from temperate zones have adapted to higher temperatures by decreasing body size.

Can we recover what is lost?

Tens of millions of years of this unique evolutionary history are carried in the genes of animals and scientists are just beginning to glimpse ways to unlock the hidden treasure. Advances in science mean we can recover ancient genomes and so, potentially, lost species. The technology is still developing and will require ethical and environmental consideration. “No other continent can claim a similarly unique library of genetic information in the way that Australia can,” Archer says, arguing that Australians have a “greater responsibility for securing the world’s genome than anywhere else in the world”.

For example, Archer says the genetic information, or genome, of koalas and wombats – one another’s closest living relatives – represent a staggeringly diverse range of marsupial species that once walked the Earth, including the largest marsupial ever, the giant wombat-like diprotodon optatum, and the marsupial lion.

“All of these genomes are probably represented, at least in significant part, within the living genomes of the koala and the wombat. So they’re more than what they represent in their own right – because every animal on Earth has a genome that has a staggeringly huge amount of silent genes that relate to its ancestry. And the more we understand about gene manipulation – and that’s happening very fast – the ability to reach into the living animals’ genomes and recover ancient genomes becomes very, very exciting.

“We begin to keep our fingers crossed that what we’ve lost may not have to be lost forever.”

“Koalas have a special antibiotic in their pouch that helps to keep their youngsters free of diseases.”

Archer has started a project to try to recover the Tasmanian tiger – “and what we’ve discovered is we now have the whole genome, all the information, we technically need to do that”.

There are other good reasons to preserve existing species. “Koalas have a special antibiotic in their pouch that helps to keep their youngsters free of diseases but it’s not a class of antibiotics we’ve ever seen or that we’re used to using,” says Archer. “So reaching into the koala, in effect, to find out what is this antibiotic that it’s making – and what are the genes that are doing it – could be extremely important for us.”

Australia has been a continent-sized sanctuary for millennia but for the past 230 years species have disappeared quickly and consistently. Nascent genetic technology to recover lost species is exciting but it won’t fix a key cause of extinctions: habitat loss. Political will is required to drive reforms of our laws on the environment and planning.

No Comment